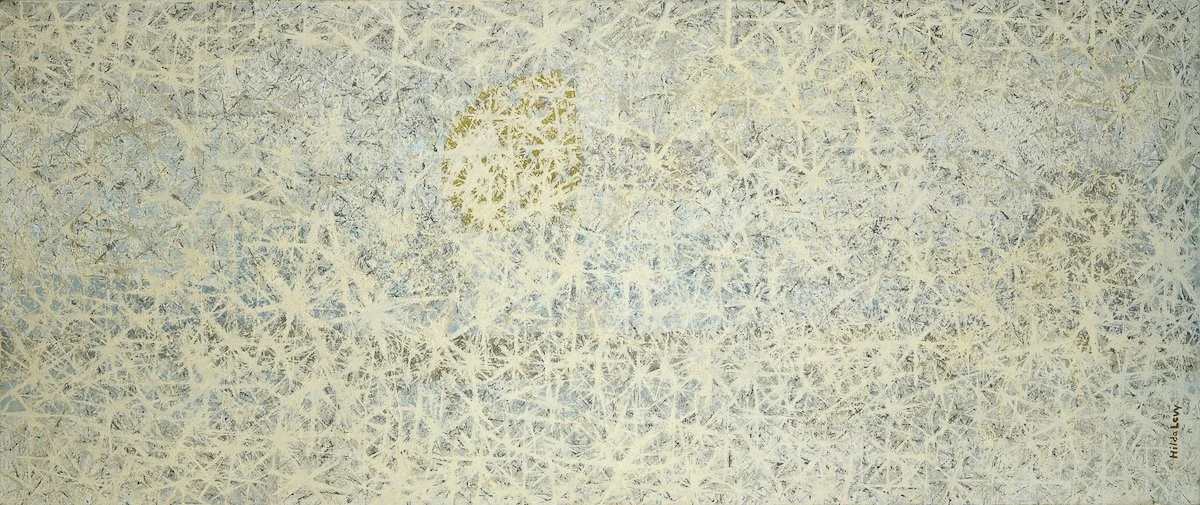

the Seeker

Hilda Levy

American Abstract Expressionist

B/D

1908—2001

Hilda D. Levy, née Hilda Dorothea Mirsky, was born in Pinsk, Russia, and gained significant acclaim as an abstract expressionist during the 20th century. She immigrated to the U.S. with her sister and older brother, and they met up with their father shortly after WWI. Tragically, Hilda’s mother died just about the time the ship to America arrived. Based on Ms. Levy’s journal notes, it would seem she was interested in honoring the positive influences in her life with her art. She mentions that she had a “desire since a child to express myself in some way.”

“For an individual to have insight into his own being, he needs to have knowledge of his past as it existed and was handed down through his family—that is, that part of it with which he had contact directly or indirectly. It is for this reason and also for the urgent desire since a child to express myself in some way, that I venture at last into a thrilling adventure. ... My aim, therefore, is to acquire a sufficient skill [as a painter] to enable expression of past events in our family history.”

— Excerpt, Hilda’s Journal, March 26, 1947

After immigrating to America, Hilda lived in Massachusetts before settling in California and studied art at UCLA, the Jepson Art Institute in Los Angeles. She also obtained a degree in social work at UC Berkeley. Soon after graduating, she married Joseph Levy, and for most of their life, they lived in Pasadena. Curiously, Hilda’s husband, like Cameron’s, was a scientist at Caltech. He was immensely supportive of her work, building crates for her extensive art exhibits (44 in total) to be shipped, and built frames for her canvases. Being married to scientists perhaps added to the fundamental change in perception and expression of both her and Cameron’s artwork. Although Cameron’s portrayals are rooted in myth and esoteric influences, both women sought their autonomy.

Interestingly, Hilda had a one-woman show at the renowned Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles in 1957, prior to the Wallace Berman show, where one of Cameron’s drawings caused the gallery to be closed by the vice squad. It’s not known if these two amazing women ever met.

Hilda Levy worked quite consciously on issues such as how to show depth in a non-representational work.

Hilda Levy with her husband Joseph Levy, presenting her painting Essences #7 (1966, oil on canvas), later sold to Dr. John Thie and reported stolen.

“The visual arts offer the possibility to keep open these channels for true experience through revelation. This involves a process of becoming. The process of continuous change, or metamorphosis, is truly man’s link with the Universe. This vision being metamorphic, how can the artist define his art? The nature of the creative self is so elusive, unknowable! The truth of the now stands by the side of a further revealment of the tomorrow.

A painting is telling of a creative act or of a non-creative act.”

— Hilda Levy, as told to Edward Reep, The Content of Watercolor, 1969

Hilda’s cosmic capturing of this concept is remarkably seen in her Circular Depression Series, where her abstractions convey strong structures with space exploration, or in her Formulations Series using watercolors and ink on heavy crepe-like hospital paper used to wrap instruments during her daughter’s lengthy stay in the hospital for severe burns. Her brilliance lies in working with non-objective forms and spatial extensions.

Her son, Jack Levy, explains that his mother’s commitment to Abstract Expressionism—other than a few of her paintings—meant that “all are meant to be hung in any of the four orientations.” He notes that “most are signed on the verso rather than the recto so as not to bias the presenter in the choice of orientation.”

Jerome Allan Donson, Director of the Long Beach Museum of Art in Long Beach, California, wrote that Hilda, “has utilized linear and rectangular forms which float in a forward picture plane and create an impressive intellectual and aesthetic effect.” Certainly, Hilda’s dedication to her craft and inventive use of materials left a lasting impact on the evolving 20th-century art scene. She employed lacquer over her paintings to create this aesthetic effect that added shine to her work.

Hilda stopped painting in the late 1960s to care for her ailing husband. It was not until ten years after his death in 1972 that she began to sculpt. To this day, none of her sculptures have been exhibited. Hilda died at the age of 92.

During her lifetime, Hilda D. Levy was listed in the Archives of Contemporary Art, Museum of Modern Art, São Paulo, Brazil; Who’s Who in American Art; Archives of the California State Library, Sacramento; Archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and Western Branch of the Archives of American Art, Oakland Museum. Her work was reviewed in Art News and Art Forum. Her painting entitled Number Six can be viewed at the Norton Simon Museum.

“The fulfillment of the painting is the sensing of its particular flow as a truth. Only this experience can give the work a life of its own.”

— Excerpt, Hilda’s Journal, May 1952

ARTWORK

Bird In The Forest, ink and watercolor, 14 1/2" x 9 3/4".

In the Silence VI, 1965, oil on canvas, 72" x 30".

Blue Space, 1958, oil and collage on board, 48" x 38".

Celestial Affinities II, 1977, oil on canvas, 60" x 48".

Circular Depression Series #16, 1963-64, watercolor and pastel, 30" x 40".

Fugue in the Silence #36B, 1966, watercolor on hospital paper, 20" x 20".

City in a Holiday Mood, 1955, casein on board, 36" x 22".

Essences #8, 1966, oil on canvas, 30" x 72".

In the Silence Diptych, 1966, oil on canvas, 48" x 60".

Phantasmagoria, 1955, ink and collage, 15" x 22".

Pulsation XXVI, 1961, white gouache on black rice paper, 24" x 30".

Origins VI, 1962, oil on canvas, 30" x 72".